- Home

- Dayna Lee-Baggley

Healthy Habits Suck Page 2

Healthy Habits Suck Read online

Page 2

It was eye-opening to realize I was experiencing what so many of my clients had described: that their efforts to be healthy, lose weight, or control blood sugar had no effect. It was humbling to have to provide obesity-management treatment to individuals and groups when I myself was forty pounds overweight. I felt like a fraud, and I found myself needing a reason to continue being healthy when it seemed to have no effect on my weight. I began using all of the techniques and tools I’d been providing clients for years. I had to “walk the walk” so I could continue to stand in front of individuals and groups and encourage healthy living, even if my body didn’t show it.

This is all to say that I didn’t write this book as someone who has it all figured out. At the time of this writing, I still haven’t lost all my “divorce weight,” and I still continue to engage in healthy behaviors. As I have learned to say to myself: I live as healthy as possible; what my body does with it is not up to me. So, not only have many of the suggestions in this book been field-tested on clients, they’ve also been tested by me. As someone who would much rather lie on the couch and eat ice cream, I’m on this journey with you.

That’s the broad abstract for the book. Here’s an overview of the topics we’ll explore:

Part 1: Being Healthy Is Hard

Identifying values and how they can motivate us to do the hard work of being healthy (chapter 1)

Recognizing what we do and don’t control, and learning how to focus on what we do control (chapter 2)

Part 2: How to Be Healthy…Even if You Don’t Want To

How to deal with thoughts and feelings that get in the way of engaging in health behaviors (chapters 3 and 4)

How to use mindfulness and self-compassion skills to engage in health behaviors (chapters 5 and 6)

Part 3: Living a Healthy Life

How other people impact our lives and how to deal with those who may help or hurt our health behaviors (chapter 7)

How to handle relapses in health behaviors (chapter 8)

How to integrate health behaviors in the long term (chapter 9)

Your Healthy Habit

In order to make working through this book as practical as possible, I suggest that you pick one healthy habit to focus on, such as going to the gym, eating more fruits and vegetables, or reducing sugar consumption. It should be a habit you haven’t been able to successfully stick to. In each chapter you’ll learn different skills to help you improve your chances of sticking with it. These skills build on each other, and by the end of the book you’ll have a whole toolbox full of skills to help you live a healthier life.

In this book we’ll be using an adaptation of the choice point model (Ciarrochi, Bailey, and Harris 2013) to help you stick with this healthy habit. This model outlines how with any challenging situation you can move toward or away from what matters to you. In this book, you’re going to focus on moving toward your healthy habit. There will be things that get in the way of you engaging in this healthy habit, so you’ll be learning a bunch of skills that will help you stick to it more often. The goal of this model is to help you give yourself a choice point, which is a conscious, deliberate choice to engage in a heathy habit and move toward what matters to you. Often we behave automatically, engaging in unhealthy habits without fully being aware of doing so. The goal of this worksheet and this book is to help you make more conscious choices for your health.

You can download a copy of the choice point worksheet at http://www.newharbinger.com/43317. You can write down the healthy habit you want to work on at the bottom. You can choose any healthy habit that is important to you. For example, you might write “exercise more” as the healthy habit you want to work on. At the end of each chapter I’ll ask you to add to this worksheet what you learned in the chapter. By the end of the book, your copy of the worksheet will include all the skills you’ve learned that will help you engage in your healthy habit, as well as the things that can get in the way. I recommend reading one chapter a week and doing its exercises and practicing its skills during that week. Each chapter builds on the one before it, as do the skills. By the end of the book, you’ll be better equipped to stick with your healthy habit because of all the choice points you’ll be able to give yourself.

Lastly, a host of online accessories (worksheets, exercises, and audio scripts) that augment the content of this book is available for download at http://www.newharbinger.com/43317. See the back of the book for details about accessing this material.

So, in this book I’m not going to try to make health behaviors easier, because I can’t, but I am going to offer you skills to motivate yourself to be willing to undertake the difficult acts of being healthy—even when you don’t want to.

Part 1:

Being Healthy Is Hard

Chapter 1:

The Marathon Runner Who Hated Running

In my efforts to lose my divorce weight, I decided to join a running club. One day I found myself running with a man who was turning seventy. He was a much better runner than me, and despite our age difference I had to keep asking him to slow down! While discussing the topic of running, he said to me, “Oh, I don’t enjoy running.” This came as quite a shock, considering he had already run more than a dozen marathons. He explained, “I don’t actually enjoy the act of running. But I really enjoy being a runner.” He said he felt quite accomplished and proud when he told other people that he runs marathons. Thus, this man who had run more than a dozen marathons didn’t like running, and yet he kept running because he had found something important and meaningful in the act.

Why on Earth Would You Engage in Health Behaviors?

Have you chosen a healthy habit to work on that you haven’t successfully stuck with? Whatever you’ve chosen, I’m willing to bet it’s something that goes against our human instincts. As I noted in the last chapter, millions of years of evolution have shaped humans to avoid pain, seek pleasure, take the path of least resistance, and live for today. Over time, these strategies became instincts that showed up automatically, and they were tremendously helpful for our early ancestors, as they still can be today. For example, if you accidentally put your hand on a hot stove, your instincts jump into action, and you take your hand away from the source of pain without conscious awareness. Your hand moves before you even register the pain. This is an ancient instinct at work.

Let’s examine some typical healthy habits to see if they violate our instincts. Eating more vegetables? Yup, sure does: seeking pleasure. There are no receptors in your brain that respond to vegetables like they do for sugar. Going for a walk? It violates the instinct to take the path of least resistance. No matter how many times you go for a walk, it will always take more effort to walk than to lie on the couch. Training for a marathon? This completely violates the instinct to avoid pain. Avoiding junk food? Yes, indeed. This violates the instinct to live for today. Almost every health behavior goes against your natural instincts, and therefore health behaviors suck. They inherently don’t feel good. So why on earth would you engage in health behaviors if they suck so much?

Values

Values are the qualities and characteristics that we would most like to express and represent in our lives; they are what matter most to us; they represent how we want to engage with the world. Values aren’t just a thing, a noun, such as “parent.” They include qualities, such as being adventurous, caring, creative, resilient, and persistent. A value is being an engaged parent, a compassionate spouse, an artistic worker. Values also have an emotional resonance: they just feel right. You don’t have to explain why a value matters to you, you just know.

Western culture is very focused on goals, which are different from values. Goals are things that happen or don’t happen. Once we achieve a goal, we usually stop pursuing it and move on to a new goal. For example, let’s say you have the goal of losing weight, so you go on a diet. If you reach your goal weight, then what do you do? Many p

eople stop doing whatever it is they were doing to lose weight. This is entirely consistent with the notion that when you achieve a goal, you move on to a new goal and stop working on the goal you just achieved. Do you see the problem? If you stop engaging in the health behaviors that resulted in weight loss, you’re likely to regain the weight.

Unlike goals, values are more like a direction you head in. Imagine that heading west is an important value of yours. You might hit certain landmarks or cities along the way that will let you know you’re headed west, but these markers (goals) alone aren’t all that matters—every step heading west matters. Also, you’d never be able to “get west” in the goal sense. If heading west was a value, you’d always be trying to head in that direction.

Here’s a less abstract example: if being a caring and loving person is a value of yours, then you have to continue to express that value all the time, such as by kissing your child or telling your husband you love him daily. You may hit markers along the way that let you know you’re living this value, such as getting married, but you could never say, “Well, in 1985 I was super kind to my sister, so I’m good.” Values don’t work that way; you have to keep expressing them.

Let’s briefly explore your values. I assume that you’re reading this book because you want to be healthier, so answer this question for yourself: Why do you want to be healthier? Most people say they want to feel better, be more confident, have more energy and be more active, live longer, or avoid some bad health outcome (for example, diabetes, heart disease, cancer). Does your answer fall along these lines? The problem is we often don’t go any deeper than this by asking, What am I going to do what that extra energy, confidence, health, and longevity? The way you answer this question helps reveal what really matters to you—your values (for example, traveling, exploring, dancing, playing music, and so forth).

I had such a discussion with a woman living with obesity who really wanted to stop eating her favorite snack, jelly beans, so she could lose weight. I started with the standard question: Why do you want to lose weight? And she gave the standard answer: “So I can be healthier.” I probed further: Why do you want to be healthier? “So I can be more active.” Why do you want to be more active? “So I can be healthier and lose weight.” We went around in circles like this, yet I continued to press: What will you do with better health and extra energy? “I’ll be able to walk stairs better. It hurts too much right now to do stairs.” And what matters to you about being able to walk up stairs better? With this question, she suddenly burst into tears and said, “I have to move out of my family home because I can’t walk up the stairs.” Through her tears she explained, “This is my dream home. I’ve lived in it for forty years. I raised all my children there. I wanted to spend the rest of my life there…but I can’t because I can’t handle the stairs anymore.”

I was in tears at this point, too. That she had to give up something that meant so much to her because of her health was so poignant and painful. Just “wanting to be healthier” may not make giving up jelly beans worth the effort, but wanting to stay in her dream home just might be. (The “Clarify Your Values” exercise, available for download at this book’s website, http://www.newharbinger.com/43317, can help you sort through your values.)

Linking Values and Health Behaviors

You’ve identified some of your values and the healthy habits you want to engage in. Let’s work to link one of your values with one of your health behaviors. You can download the “Linking Values and Behaviors” worksheet at this book’s website: http://www.newharbinger.com/43317. Remember, the goal is not to make “health” or “fitness” or “being active” a value. Real sustained change happens when we’re able to link a health behavior to an existing, deeply felt value.

Ask yourself these questions:

How will engaging in the health behavior help me move toward a value?

How does engaging in the health behavior help me express a value?

Why does this health behavior matter? And what matters to me about that?

Here are some examples of ways to link a value and a health behavior:

Directly linked: When I go for a walk I’m expressing my value of contact with nature.

Means to an end: If I eat more vegetables, I am at a healthier weight, and if I’m at a healthier weight then I’m funnier and more sociable (value = humor/engaged relationships).

Think outside the box: I value honesty. I need to track my food to be honest with myself about what I’m eating.

I follow a plant-based diet. It’s similar to a vegan diet (no dairy, no meat) but focuses on what I do eat rather than what I don’t eat. It’s supposed to improve my health, but that’s really just a bonus. The main reason I started this diet has to do with climate change. Reducing my contribution to this phenomenon is important to me. It turns out that the agricultural industry related to meat production typically contributes more greenhouse gases per person than does driving a car. That’s to say that eating animal-based foods was probably generating more greenhouse gases than driving my car. For me, linking the value of “doing my part to reduce greenhouse gases” to this diet motivates me to stay on it, and the diet has the side effect of being a healthy choice for me.

Here’s an example of how a client of mine linked behaviors and values. He came to see me to learn how to better manage diabetes. He knew he should be doing healthy things, but he never seemed to get around to them. Specifically, he wanted to get on the treadmill every morning (his health behavior). Here’s the discussion we had:

Me:What about getting on the treadmill is important to you?

Client:My sugars are better. My day is generally better. I have more energy.

Me:Why is it important to you to have more energy?

Client:So I can do more things. So I can be more prepared.

Me:So when you have more energy you tend to be more prepared? And what is important to you about being more prepared?

Client:Things go more smoothly.

Me:What is important to you about things going more smoothly?

Client:People around me are happier. I get along better with my family. I can enjoy them more.

Me:And it matters to you to have good relationships with your family members?

Client:Yes, very much.

Me:So getting up in the morning is not just about managing your sugars. It’s also about your values regarding getting to enjoy your family more.

Through this inquisitory process he and I were able to link his stated health behavior with values, and this connection allowed him to better stick to getting on the treadmill—even when he didn’t want to.

Apple Pie Will Always Taste Better Than Apples

What tastes better, apple pie or apples? Uh, apple pie. You may eat a healthy diet such that the sugar and fat in apple pie is a shock to the system, and you may feel quite tired and yucky after eating apple pie, but your brain is hardwired to get excited about sugar and fat (apple pie) and not apples. What feels better, lying on the couch or going for a run? Lying on the couch! Again, your brain is hardwired to prefer the path of least resistance. It doesn’t matter if you’re a triathlete. You may get used to expending energy in a certain way, but it will always take more energy to go for a run than it does to lie on the couch.

All health behaviors have pros and cons. Pros include things like improved mood, more energy, or being able to stay active with grandkids. Cons include things like expending effort and being sweaty and uncomfortable. Research shows that when the pros outweigh the cons, you’re more likely to engage in and stick with a health behavior (Hall and Rossi 2008).

There are different ways to make the pros outweigh the cons. One option is to make the pro side “heavier.” Another option is to make the con side “lighter.” People in your life (especially your health care providers) may try to make the con side lighter by trying to convince you that

a health behavior isn’t that bad (“After a while you won’t notice the side effects of your medication” or “You’ll get a runner’s high and feel so good!”). I know many physiotherapists who recommend that their patients find an exercise they enjoy—that is, find an exercise with fewer cons to it. Well, many of us (including my marathon-runner friend) don’t enjoy exercise. I have run a half marathon and more than a dozen 10Ks, and I have never had a runner’s high. So I say that it’s totally okay to hate every minute of exercise. You don’t have to find an exercise you’ll enjoy. Your exercise can continue to suck. We don’t have to decrease the cons of the behavior in order to do it. Instead we can increase the pros.

You can dramatically increase the pros of a health behavior by linking it to your values—to what makes it worthwhile to you. In fact, research supports the benefit of this (Hall and Rossi 2008). The reasons for doing the behavior become more meaningful as a result and have a stronger pull. It’s always going to take effort to exercise, so rather than trying to convince yourself that the health behavior won’t be that bad, you should acknowledge how much the health behavior sucks and figure out what will make it worth it for you.

We Do Difficult Things All the Time

I was working with a woman who was having a hard time quitting drinking. Quitting was really important for her because she had a liver condition, and alcohol was very detrimental to her health. We talked about why she wanted to be healthy. She said she wanted to have more energy (a typical response). “What will do you with that extra energy,” I asked. She said she would use it to clean up her house, to do her dishes and her laundry. I stared at her. “You mean we’re doing all of this work just so you can do more laundry? Well no wonder you don’t want to quit drinking. I wouldn’t quit drinking either if it meant I was going to have to do more laundry.”

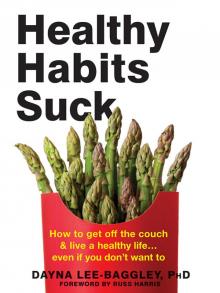

Healthy Habits Suck

Healthy Habits Suck